Philosophy is pretty unpopular in America today. Marco Rubio says, with typical inelegance: «We need more welders and less philosophers.» Governor Pat McCrory of North Carolina also singles out philosophy as a discipline offering «worthless courses» that offer «no chances of getting people jobs.» Across the nation there’s unbounded adulation for the STEM disciplines, which seem so profitable. Although all the humanities suffer disdain, philosophy keeps on attracting special negative attention — perhaps because in addition to appearing worthless, it also appears vaguely subversive, a threat to sound traditional values.

Such was not always the case. Throughout its history in Europe, philosophy has repeatedly come in for abuse from the forces of tradition and authority. The American founding, however, was different: the founders were men of the Enlightenment, steeped in the ideas and works of Rousseau, Montesquieu, Adam Smith, and the ancient Greeks and Romans — especially Cicero and the Roman Stoics. As men of the Enlightenment they took pride in steering their course by reason and argument rather than unexamined tradition. Their intellectual independence and theoretical thoughtfulness served them well when it came to setting up a new nation. We’ve traveled a long way from those roots, and not in a good direction.

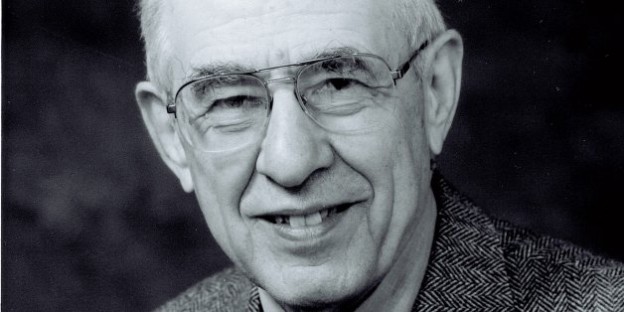

On March 13, America lost one of the greatest philosophers this nation has ever produced. Hilary Putnam died of cancer at the age of 89. Those of us who had the good fortune to know Putnam as mentees, colleagues, and friends remember his life with profound gratitude and love, since Hilary was not only a great philosopher, but also a human being of extraordinary generosity, who really wanted people to be themselves, not his acolytes. But it’s also good, in the midst of grief, to reflect about Hilary’s career, and what it shows us about what philosophy is and what it can offer humanity. For Hilary was a person of unsurpassed brilliance, but he also believed that philosophy was not just for the rarely gifted individual. Like two of his favorites, Socrates and John Dewey (and, I’d add, like those American founders), he thought that philosophy was for all human beings, a wake-up call to the humanity in us all.

Putnam was a philosopher of amazing breadth. As he himself wrote, «Any philosophy that can be put in a nutshell belongs in one.» And in his prolific career Putnam, accordingly, elaborated detailed and creative accounts of central issues in an extremely wide range of areas in philosophy. Indeed there is no philosopher since Aristotle who has made creative and foundational contributions in all the following areas: logic, philosophy of mathematics, philosophy of science, metaphysics, philosophy of mind, ethics, political thought, philosophy of economics. philosophy of literature.

And Putnam added at least two areas to the list that Aristotle didn’t work in, namely, philosophy of language and philosophy of religion. (Philosophy of religion because he was a religious Jew, and he understood Judaism to require a life of perpetual critique.) In all of these areas, too, he shared with Aristotle a deep concern: that the messy matter of human life should not be distorted to fit the demands of an excessively simple theory, that what Putnam called «the whole hurly-burly of human actions» should be the context within which philosophical theory does its work.

That commitment led him to oppose many fads of his time: for philosophy is prone to simplifying and reductive fads, from logical positivism to a later fad for computer modeling of philosophical problems. Putnam knew physics like virtually nobody else in the field, and so he also knew that it was fatal to reduce philosophy to physics: philosophy is a humanistic discipline. (I remember a marvelous and profoundly countercultural course he taught at Harvard, in the days when logical positivism was just beginning to wane, entitled «Non-Scientific Knowledge.» It covered ethical knowledge, aesthetic knowledge, and religious knowledge, and Putnam showed the folly of imagining that physical reductionism could replace those normative subjects.) His independence from fads also led him to take a keen interest in the thought of the ancient Greeks, who looked stupid to the positivists but who actually had a few good ideas! He learned ancient Greek in order to work seriously on Aristotle, and he argued that Aristotle had important insights about the mind-body relationship that contemporary thinkers ought to take up.

At the same time, and again like Aristotle, Putnam never gave way to irrationalism, never took up a skeptical and dismissive attitude to philosophical theorizing: for, as he stressed, the attempt to order our world by the work of reason is one of the most deep and pervasive aspects of the hurly burly of human life. He believed that we are always prone to not just messiness and sloppiness, but, worse, to capitulation to forms of authority and pressure, and that the work of philosophy was needed to counter these baneful tendencies.

Most philosophers talk a lot of talk about following the argument, but eventually lapse into dogmatism, defending a well-known position at all costs, no matter what new argument comes along. The glory of Putnam’s way of philosophizing was its total vulnerability. Because he really did follow the argument wherever it led, he often changed his views, and being led to change was to him not distressing but profoundly delightful, evidence that he was humble enough to be worthy of his own rationality. Once in the late 1970’s he offered a class on metaphysics at Harvard with his colleagues Nelson Goodman and W. V. O. Quine. The other two held views very different from Putnam’s, and they argued well. Putnam became more and more excited by the debate — so much so that he would leave a department meeting in the middle of lunch to walk up and down the halls with Goodman. At the end of that term, his Presidential Address to the American Philosophical Association contained an elegant argument against himself — somewhat in Goodman’s spirit, though not exactly.

A life in reason was and is difficult. All of us, whether we are ignorant of philosophy or professors of philosophy, find it easier to follow dogma than to think. What Hilary Putnam’s life offers our troubled nation is, I think, a noble paradigm of a perpetual willingness to subject oneself to reason’s critique. Our country, founded by lovers of argument, has become the plaything of rhetoricians and entertainers (characters that Plato knew all too well). On this day when we have lost one of the giants of our nation, let’s think about that.

Este artículo fue originalmente publicado en The Huffington Post, el 14-3-2016. Puede consultarse aquí.

Aquí una traducción: http://filosofiadecuento.blogspot.com.es/2016/03/martha-nussbaum-se-despide-de-hilary.html